A man in the shadows, the cruising genius

Kégresse: a genius engineer

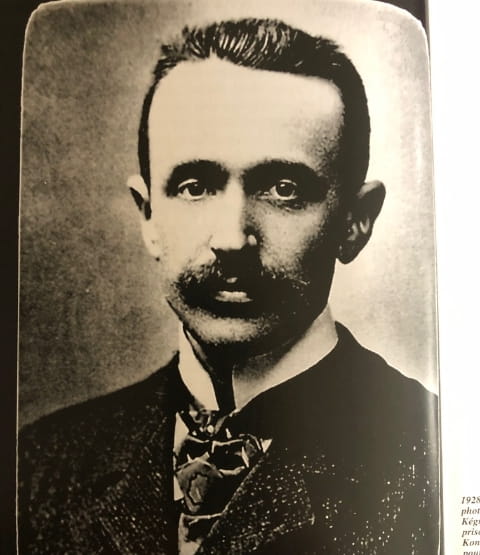

Adolphe Kégresse, the life journey of an unheralded genius

Adolphe Kégresse, the big thinker

André Kégresse's life has many romantic overtones. He was the son of Gustave Adolphe Kégreisz, the director of a spinning mill in Héricourt, between Montbéliard and Belfort, and Sophie Emilie Buchter, a cloth merchant. A clerical error on his birth certificate dated 2 June 1879 led to him being given the surname Kégresse. The boy grew up with a passion for mechanics. At the technical and industrial college in Montbéliard, where his parents enrolled him, his talents were honed. During his military service, he fitted an engine to a bicycle, thereby creating one of the very first mopeds in history. It was his first invention. There were to be others. Back in Héricourt, he started work at Jeanperrin, a small car manufacturer. He quickly climbed the ladder, but André Kégresse dreamed of a new world...

An adventurer at the service of Tsar Nicholas II

Pushed into it by a fellow countryman, he headed for Russia in 1903. In St Petersburg, the railway company took him on as a senior mechanic. It was there that his destiny changed. One morning, while working on the tracks, the imperial train, with Tsar Nicholas II on board, came to a standstill on a turntable blocked by frost. He stepped in and unblocked the switch. His action was spotted by a member of the royal entourage, who decided to employ him as a mechanic in the Tsar's garages. Everyone praised the quality of his work, but also his inventiveness and his personality. Adolphe Kégresse was discreet, available and unfailingly honest. His qualities were rewarded when, in 1905, he was appointed technical director of all the Tsar Nicholas II's automobile services. He became the head of a team of around twenty mechanics. His close relationship with the imperial family was confirmed when the Tsar led him to marry Héléna Moniakoff, the widow of an imperial army officer. This marriage produced Sonia in 1904, Elisabeth in 1906 and Valentin Adolphe in 1908.

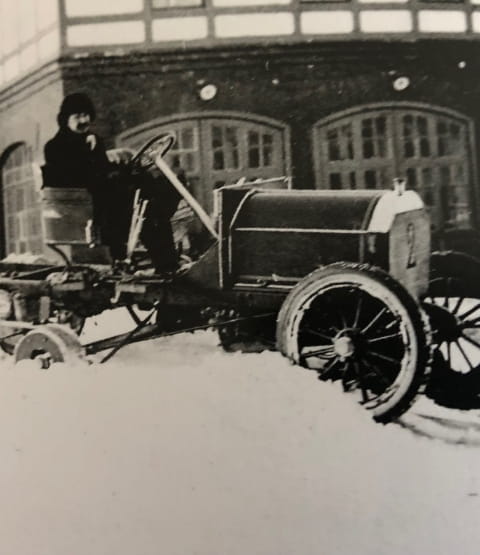

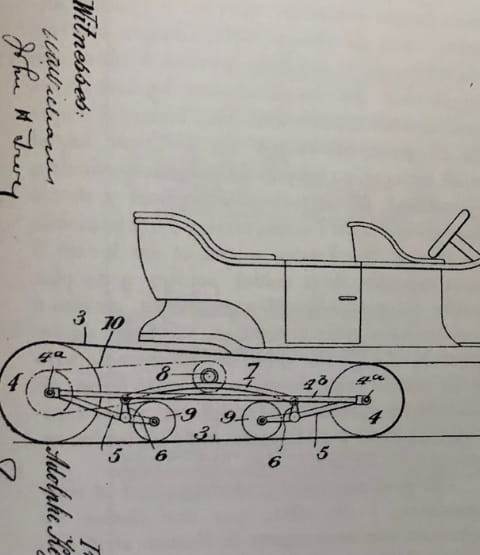

His mission was not limited to maintaining the imperial motor fleet. He was asked to find a solution that would allow the Tsar to continue hunting wolves in winter. The deep, soft snow caused vehicles to get trapped at their running boards. It was then that he came up with the idea of attaching skis to the front axle and installing a belt on the rear axle to propel the vehicle effortlessly over snow and off-road. His system was perfected and patented in 1913, giving rise to the flexible track.

Adolphe Kégresse & André Citroën, the life-changing encounter

After serving in the Russian army at the outbreak of the First World War, Adolphe Kégresse was forced to flee Russia with his family at the start of the Bolshevik revolution. He found refuge in Finland. His situation did not suit him, and he returned to Héricourt in 1919 with only his patent for flexible tracks to show for it. At his request, Georges Schwob d'Héricourt, a businessman and engineer who had chaired the Citroën gear company, introduced him to Jacques Hinstin, Citroën's exclusive dealer for the Seine et Oise region and André Citroën's partner in the gear company.

On a crisp October morning in 1920, André Citroën attended a demonstration of three Type A cars fitted by Hinstin with Kégresse caterpillar tracks on rough terrain in Saint-Denis. Immediately won over, Citroën declared ‘this invention is mine’. He secured exclusive rights by registering a patent under the name ‘Citroën-Kégresse-Hinstin’. An Autochenilles department was created, and spectacular demonstrations were soon organised in the Alps and the Pyrenees. Kégresse's invention contributed to the brand image of the ‘chevron’ firm. Kégresse made headline news when he climbed the steps of the Hôtel Régina at the wheel of a Citroën equipped with caterpillar tracks. The Kégresse tracks opened up new prospects for the Quai de Javel firm. What a publicity coup: the caterpillar system opened the way for Citroën to embark on major expeditions. The Sahara crossing in December 1922 was followed by the Black Cruise, from 1924 to 1926, and then the Yellow Expedition, from 1931 to 1932. These expeditions would not have been possible without Adolphe Kégresse, who developed the vehicles. One of Citroën's closest collaborators, the engineer from the Franche-Comté region travelled the world to demonstrate his system.

The post Citroën era: the end of the road for the track

When Michelin took over the chevron brand, it dissolved the track department. Kégresse left the company with his mechanics and founded SEK (Société d'Exploitation Kégresse) in 1935. The company embarked on a number of projects, including the development of an automatic gearbox and the sale of the track patents to the United States, giving rise to the Half Track.

In June 1940, after the rout of the French armies, Adolphe Kégresse went into exile in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Adolphe Kégresse had values on which he would not compromise: for fear that his plans would fall into the hands of the occupying Germans, he preferred to destroy them. He eventually returned to his house in Croissy-sur-Seine, but on 11 February 1943 he died of an aneurysm. Adolphe Kégresse left an immense legacy. During his lifetime, he registered some 200 patents, mainly for automotive applications.

Ready to make you dream again?

The world's finest ephemeral garage dedicated to classic cars is closing its doors... but will be back next year for another exceptional edition! 50 years of the show! Half a century of motoring passion to celebrate together.

The ticket office is open, get your ticket!